What has given Ludwig van Beethoven’s works such resonance in popular culture?

As music professor Scott Davie sees it, there are two different Beethovens. There’s the genius known to devotees of classical music for works such as the Ninth Symphony, the opera Fidelio, and late string quartets like Grosse Fuge. And there’s the pop culture figure, the one immortalised in TikTok skits, on “Bae- thoven” t-shirts and in scenes from films like A Clockwork Orange.

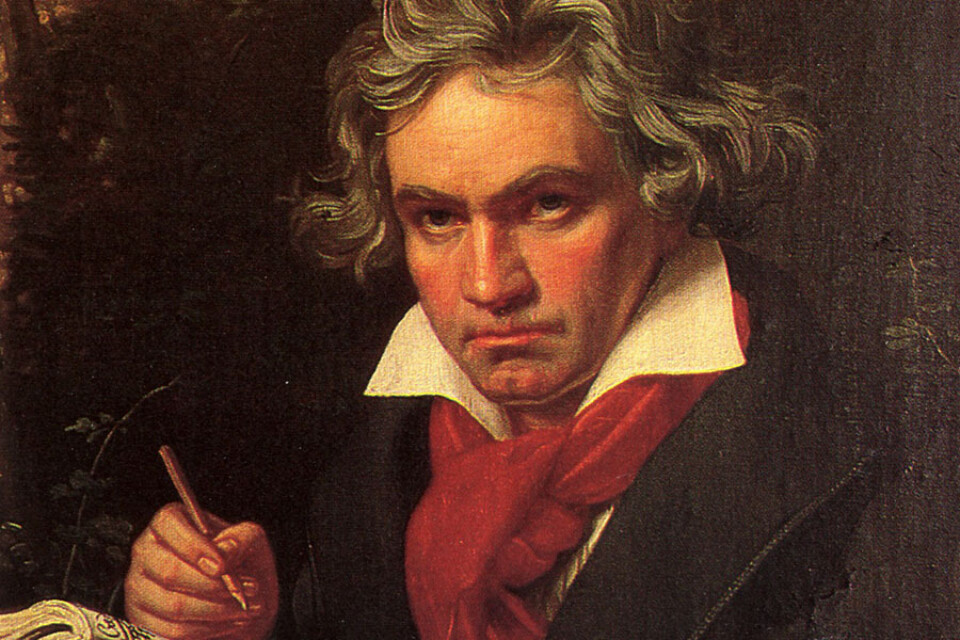

“Beethoven lives in two different ways, I suppose you could say,” says Davie, a classical pianist who also lectures in music at the Australian National University. “There’s even something that in scholarly circles is called ‘the Beethoven myth’, where the imagery that we have of him as this very strong noble face with wild hair doesn’t actually exist. So we sort of invented this character of him.”

Invented or not, the character of Beethoven is a powerful one. His name has become shorthand for seriousness and sophistication; his music an easy way to add drama to any soundtrack.

So why, out of every composer, is it Beethoven that has transcended the classical realm? Part of it, Davie says, is down to “a few lucky works” that caught the popular imagination – pieces like Für Elise and the Moonlight Sonata that resonated broadly. Beethoven stripped away the decoration that someone like Mozart might have used in favour of plain but undeniable musical structures – those famous ‘da-da-da-dummm’ notes of the Fifth Symphony a prime example.

But beyond that, he was also the first composer to redefine what a musician could be. Before Beethoven began publishing his own compositions, a composer always worked for somebody else, writing music to be used in a church or a court or at the service of aristocracy.

“I’m sure there were other composers at the time who thought, ‘I’m worth more than just writing a waltz for a court or an accompaniment for a mass’. But Beethoven was the one who managed to really put it into action,” says Davie. “He was able to show that music could be a level of philosophy – that a piece of music can have a function that is of a higher purpose.”

As Nick Bochner, Head of Learning and Engagement with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra sees it, Beethoven was the first to pioneer that idea of ‘the hero artist’ who obeyed only his muse. Not unlike the Kanye Wests or Björks of today, Beethoven stubbornly set out to make the music he wanted to make, whether or not audiences of the day appreciated it. He was also one of the first to use music to create an “enormous, dramatic arc” that tells a story, an approach that directly inspired greats like Tchaikovsky and Mahler. But it’s also had modern-day consequences: “I don’t think film scores would be where they are now if it wasn’t for Beethoven, demonstrating how you could create incredible storytelling [with music],” says Bochner.

While Beethoven enjoyed significant success in his lifetime – he was the “hot young thing” in Vienna around the turn of the 18th century, Davie says – he had some foresight over the fact that his works’ greatest appreciation would happen posthumously.

By 1814, he had fallen into a depression, dismayed by the rise of young composers like Rossini who found great success writing music that Beethoven considered little more than a ditty. That changed his approach to composing, ushering in the period of work known as ‘late Beethoven’.

“He thought, ‘Well, maybe if Viennese society doesn’t want me, who am I writing music for?’ And in that period, he started writing for posterity,” says Davie. Many composers of the era had their work die with them – but not Beethoven.

He passed in 1827, aged 56, after a long illness. By the 1830s, artists were creating paintings and sculptures of his image that conferred the composer an almost superhuman status, spurring the beginning of the ‘Beethoven myth’ that Davie mentions. In the centuries that followed, Beethoven’s work has popped up everywhere from soundtracks of popular films to samples in rap tracks.

A great part of what has kept Beethoven at the fore of popular consciousness is simply the resonance his compositions pack. They tackle themes that transcend time: human emotion, pain, and the struggle for achievement against the odds.

“A lot of his music kind of stems from his struggle with his deafness,” Bochner explains. “These days, I don’t know which diagnosis he would have, but he wasn’t great with people.

There’s no evidence that he ever had a significant relationship with a lover of any sort. But all of his music is about overcoming all these difficulties.

Whereas before him, people were all very sort of like, oh, well, [suffering] is the will of God, this is how it should be. But for him, it’s much more like, I am going to transcend and I’m going to succeed. And that just is so well embodied in the music.

It just appeals broadly.”

Beethoven Festival

Experience the breathtaking range of Beethoven’s symphonic output in this stunning festival covering all nine symphonies of one of classical music’s most brilliant composers.

19 - 30 November

Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall

Beethoven and his cultural influence

1770

1792

1783

1795

1797 - 1812

1802 - 1812

1813 (onwards)

1814

1825 - 1826

1827

1845

1902

1940

1969

1971

1975

1977

1984

1989

2002