This article appears in the recently-published, first edition of Encore: The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra magazine.

Words: Elissa Blake

As it is for the modern-day traveller circling over Rome’s Fiumicino Airport, so it was for the French composer Hector Berlioz when he saw the city for the first time: “As I gazed down on the far-off city, standing in purple majesty in the midst of its vast desolate plain, my heart swelled with awe and reverence, and suddenly I realised all the grandeur, all the poetry, all the might of that heart of the world.”

The impressions formed in young Berlioz’s mind at that moment –and thousands of others formed on his rambles through Italy over the course of a peripatetic, adventure-strewn 15 months – would eventually be distilled into Harold in Italy, a symphonic poem in four movements that became one of the composer’s most cherished works.

“There is something about Harold in Italy that is irresistible,” says the MSO’s new Chief Conductor Jaime Martín, who will conduct the work in a program also featuring Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony. “These pieces are like the second wines from the best vintage,” Martín says. “Both composers are best known for other work but I’m really excited about pairing them together.”

Berlioz in Italy

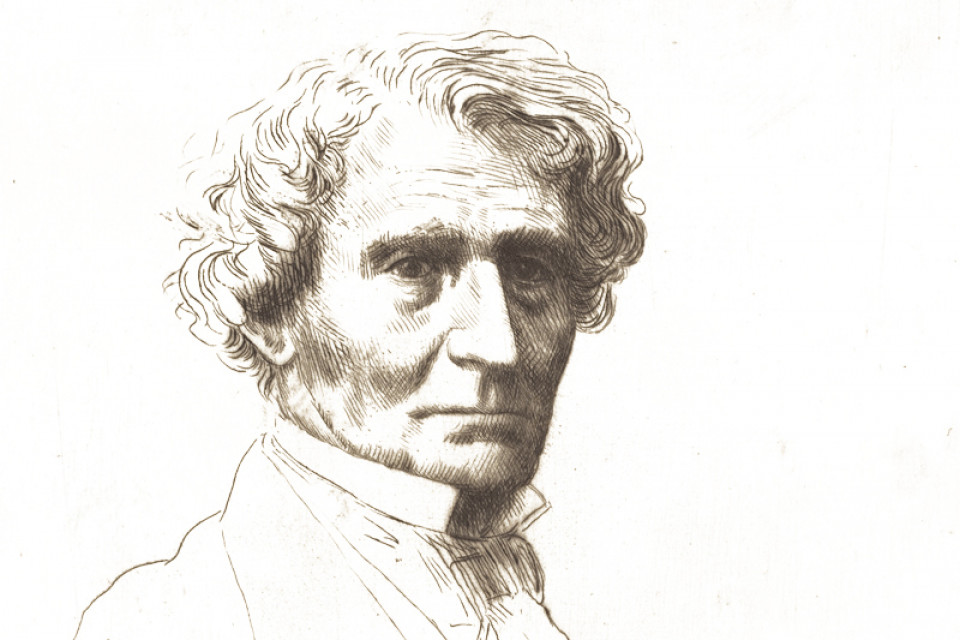

Berlioz arrived in Italy in 1831, not as a tourist but as the winner (on his fourth attempt) of the 1830 Prix de Rome, a scholarship dating back to the reign of Louis XIV providing a stipend for French artists to study the art treasures of antiquity. He was 28.

Like any modern-day award, the Prix de Rome came with outcomes to fulfill and stakeholders to manage. But Berlioz wasn’t the kind of artist used to ticking bureaucratic boxes.

“He was a very unconventional character,” says Luke Speedy-Hutton, the MSO’s Orchestra Library Manager. “When Berlioz was awarded the prize, he was not a popular composer. He had some fanatical fans and people recognised his talents but he was as eccentric in life as he was in his music.”

At first, Berlioz tried to postpone his trip. He’d just become engaged and believed his career would be better served by staying in Paris. He eventually buckled, but then baulked at the requirement to spend two years in Italy. All up, Berlioz actually stayed 15 months in Italy and spent little time in any one place.

“I have hardly ever spent more than two consecutive months in Rome,” Berlioz confessed to fellow composer Gaspard Spontini in a letter written in 1832. “I was constantly off to Florence, Genoa, Nice, Naples, the mountains, on foot, with the sole aim of wearing myself out to the point of numbness and being able to endure more easily the spleen that was tormenting me.”

(It’s worth noting here, perhaps, that early on in his stay in Italy, Berlioz threw himself into the sea in Genoa in an attempt to drown himself, having received word that his fiancée intended to marry another man.)

From his base in Rome, Berlioz travelled far and wide. He tramped through the Abruzzo region to the city’s east. He rambled the Apennines and Campania. He visited Pompeii. Inspired to write prose rather than music, he became something of a foreign correspondent. Many of his impressions were serialised in France and, later, burnished further for his book, Mémoires.

Walking from Naples to Rome, he recalled daydreaming about being “in the service of a brigand chief … That’s the life I crave: volcanos, rocks, rich piles of plunder in mountain caves, a concert of shrieks accompanied by an orchestra of pistols and carbines”.

On his way back from Naples, he recalled spending a rough night in a wayside inn, his rest plagued by “young men serenading, going round the village all night singing beneath their mistresses’ windows, to the accompaniment of … a terrible squawking clarinet”.

His daydreams and memories were to prove indelible. Berlioz returned to France in 1832 a somewhat changed man.

Sparks of genius

Harold in Italy was born two years later when, in a way, Italy came to Berlioz. In 1834 in Paris, he received a visit from an admirer, “a man with flowing hair, piercing eyes … haunted by genius”.

The visitor was no less than Niccolò Paganini, a musical superstar of his day and Genoa’s favourite son. An ardent admirer of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, he requested the composer create a work in which Paganini could display his prodigious technique and his recently acquired Stradivarius viola.

Berlioz accepted, though, as was often the case, he didn’t deliver quite what was ordered.

Drawing on his Italian sojourn and inspired by the poetry of Lord Byron – in this case the narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, published in 1812 – Berlioz (in his own words) “conceived the idea of writing a series of scenes for the orchestra, in which the viola should find itself involved, like a person more or less in action, always preserving its own individuality”.

In Harold in Italy, Berlioz breathed the gift of personality into the viola. The viola is Harold, a melancholy traveller through shifting landscapes captured in the work’s four movements.

“One of the most profound moments in the piece is right at the start,” says Speedy-Hutton. “The opening is melancholy, the first three or four minutes are really slow. You get a sense of torment, a lot of dark stuff going on. Then everything cuts out and you’re left with just the harp and the viola. It’s so simple and delicate and beautiful and that is the Harold theme. It really is quite an amazing moment.”

In the second movement, the audience hears a procession of pilgrims and tolling bells – all of which Berlioz saw and heard on his Italian journey. The third movement is a serenade – that of an Abruzzo peasant singing to his sweetheart. The riotous fourth movement, The Orgy of the Brigands, contrasts Berlioz’s fantasy of a reckless life of adventure with the more melancholy themes in the earlier movements. “It feels like you’re listening to a story,” says Speedy-Hutton. “It’s not always clear what that story is but if you listen closely to the viola, your imagination takes over.”

Harold in Italy will be performed as part of the Poetry in Music concert on Friday 19 August, and in its own right on Monday 22 August where Jaime Martín conducts Christopher Moore on viola.