Written in 1823 and first performed in 1824, Beethoven’s Symphony No.9 is often referred to as the composer’s greatest work – but did you know that he was deaf when he wrote this famous piece?

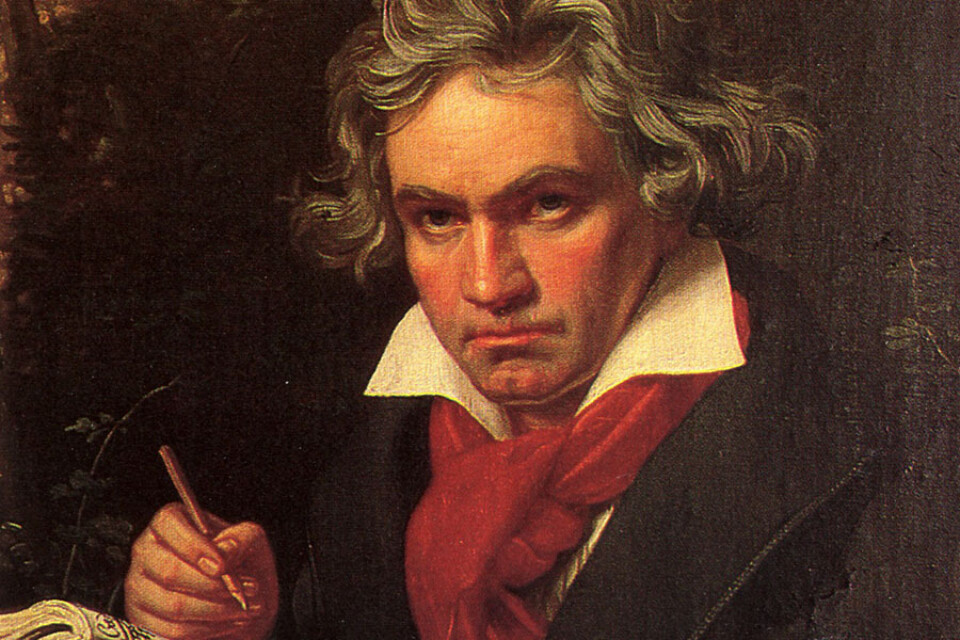

Born in Bonn, Germany in 1770, Beethoven was born into a musical family with his father teaching him piano from the age of four. However, his father’s teaching methodology and approach was often brutal and draconian. Beethoven endured a turbulent childhood, framed by the high expectations of an alcoholic father, and the early passing of his mother.

While music was the centre of Beethoven’s childhood and early adulthood, it wasn’t until around 1790, when Beethoven was in his early 20s that he really matured into a composer. At the age of 22 Beethoven moved permanently to Vienna after meeting Europe’s most famous composer at the time, Franz Joseph Haydn, who took him on as a student. But, as Beethoven flourished and gained musical notoriety, he noticed a decline in his hearing from his mid 20s. It began with a buzzing noise in his ears, and was a devastatingly scary time for the composer.

"For two years I have avoided almost all social gatherings because it is impossible for me to say to people 'I am deaf'. If I belonged to any other profession it would be easier, but in my profession it is a frightful state."

While his hearing proceeded to decline over the next 15 years, Beethoven found ways to continue to compose music. At the age of 40, Beethoven was completely deaf, yet this was when he wrote his most famous symphony – Symphony No.9, also known as The Ninth.

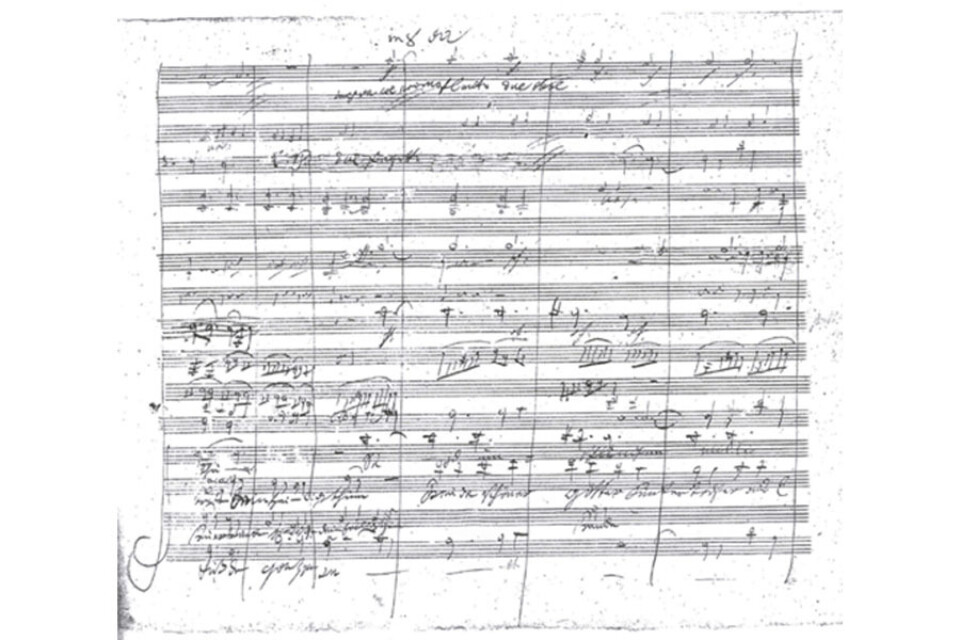

The Ninth is a complex piece, deeply rooted in Beethoven’s political will for freedom and democracy in Europe; the piece symbolises a political and societal power struggle, from dark to light – reflected through the music’s opposition of a dark minor key and brighter, more hopeful major key. Musically speaking, the symphony is classified as ground-breaking for several reasons: no previously-written symphony had the orchestral complexity and size of the piece, The Ninth was longer in duration than any other symphony ever written, and unlike any previous symphony it included vocal soloists and a choir in its final movement (the movement known as Ode to Joy).

So how was Beethoven able to compose his greatest symphony when he had lost all hearing?

Firstly, having been immersed in music since childhood, Beethoven could no doubt put together music in his mind and on paper without being able to aurally hear. By the time he was deaf, hearing music from his inner ear was innate to the great composer.

Secondly, it is said that Beethoven used techniques to physically feel music and notes in his body. This included holding a pencil in his mouth and resting it against the piano so he could feel the vibrations of the notes against his lips. The lower notes emulated a deeper vibration, therefore, pieces written in the second half of his career included fewer high notes and more low ones. There is evidence that Beethoven also cut the legs of his pianos, so that the sound vibrations resonated through the ground and into his body as he wrote his compositions! Beethoven apparently ruined many pianos in his later career from hitting the keys so aggressively in order for him to ‘hear’ what he was playing.

While the cause of Beethoven’s deafness remains unknown and debated, tests undergone on a salvaged lock of Beethoven’s hair indicated an abnormally high amount of lead. One theory is that Beethoven acquired chronic lead poisoning from the lead used in wine as a sweetener, or from the goblet he drank from, which ultimately affected his hearing.

A mere three years after the debut of his most famous work, Beethoven passed away due to the plethora of health problems he possessed, but what he left behind was an immortal abundance of rich, vibrant pieces of music, including the iconic Symphony No.9.